Feb. 5, 2016 // Shermont Edwards Receives Double-Lung Transplant

|

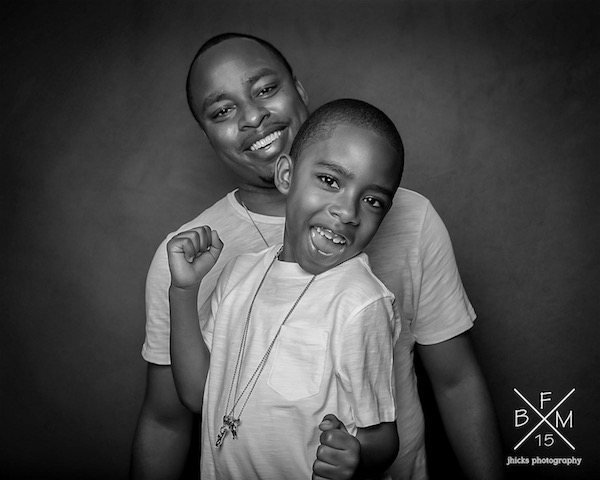

| Edwards (right) with his son, Gavin. |

Houston Center (ZHU) controller Shermont Edwards recently returned to work following a successful double-lung transplant. The cause of the 31-year-old’s lung failure started as a total mystery. Edwards has always been fit, but after a night of jogging, his back began to hurt. This continued for a month or so until it began to impact his ability to exercise. The pain became so severe that he decided to see a chiropractor. Once there, he could not actually lie on the table due to the pain, and he was sent to the emergency room where he was given Valium for the pain. His pain was subdued until he ran out of medication and the problems persisted. Edwards’ general physician suggested he may have Lupus, a chronic autoimmune disease. After processing his blood work, urine sample, and running seemingly endless tests, Edwards’ rheumatologist realized his lung function was too low and his white blood cell count was off.

“Somewhere in between the rheumatologist and the lung specialist they concluded my white blood cells were attacking my lungs and causing them to scar,” explained Edwards. “I was prescribed a number of medications to fix this but when they didn’t work, chemotherapy was suggested.”

Initially, Edwards declined the treatment out of fear, so he was sent to speak with the head of the lung department at the hospital. The lung department lead said that without further treatment, Edwards could die. This possibility hit him, “like a ton of bricks,” because he had never considered death to be a possibility for his condition. After this visit, Edwards went home and looked up the, “best lung hospital in the world.” He found the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota and booked a flight.

“I spent a week at the Mayo Clinic doing everything that I had done with the prior specialists for a second opinion,” said Edwards. “They confirmed that my lungs were in such bad shape that I would need a transplant in five years or so. They said that trying the chemo couldn’t hurt and could maybe even prevent me from needing the transplant but after numerous chemotherapy treatments, I was worse than ever.”

Edwards couldn’t go more than 10 steps without oxygen. He had to have a machine set up in his home to help him carry the tanks around with him. In November 2013, a transplant specialist informed Edwards that without a double-lung transplant, he would die. Edwards was added to the lung transplant list, for which most patients waited an average of two years. Even so, the projected success of an operation like this only has 50/50 odds, and Edwards mentally prepared for the worst. Fortunately, he received his double-lung transplant on April 16, 2014 – his son’s fifth birthday. The surgery was successful but his challenges were just beginning, as the road to recovery would be rough.

“The first week or so is a blur and I barely remember any visits or incidents,” said Edwards. “I do remember not being able to walk or talk. My vocal cords were detached somehow during the operation and from what I understand, I had lost pretty much all of the muscle in that area to the point where I couldn’t even lift my head for a month or longer. With my vocal cords damaged and nerve damage to my stomach, I couldn’t swallow or ingest anything orally. I couldn’t even have water for what seemed like forever. A couple of times a day a nurse would rub my lips with a sponge to keep them moist. All nutrition was given through a feeding tube. I had tubes coming from everywhere draining into nearby attached boxes.”

After two months of this, Edwards was finally able to stand with a walker and take steps on his own. His vocal chords were reattached in a separate surgery, but he was only able to whisper when they let him return home. After a week, his body began to reject his new organs. He was re-admitted to the hospital where he went through six-to-eight-hour long Pheresis treatments, which involved a tube being inserted into the large vein of his neck that would clean his blood through a process called intravenous immunoglobulin (IV/IG). Through this process, doctors introduced artificial blood cells from rabbits into his system, hoping that his body would not reproduce any damaged cells. After another month of treatment, Edwards was able to return home, with nearly 50 different medications of which he had to keep track.

After two months of this, Edwards was finally able to stand with a walker and take steps on his own. His vocal chords were reattached in a separate surgery, but he was only able to whisper when they let him return home. After a week, his body began to reject his new organs. He was re-admitted to the hospital where he went through six-to-eight-hour long Pheresis treatments, which involved a tube being inserted into the large vein of his neck that would clean his blood through a process called intravenous immunoglobulin (IV/IG). Through this process, doctors introduced artificial blood cells from rabbits into his system, hoping that his body would not reproduce any damaged cells. After another month of treatment, Edwards was able to return home, with nearly 50 different medications of which he had to keep track.

In addition to the challenging recovery, Edwards is diabetic, and had to check his blood sugar four times a day and inject insulin two times a day. He also had to inject himself twice a day in the stomach with medication to clear up a blood clot that had developed in his chest following the transplant. A nurse came to his house for the next four months to continue the IV/IG treatments. He went to physical therapy three times a week to strengthen his body so he could do the everyday things most people take for granted, like bathing and dressing without assistance. In addition, the doctors ordered routine blood work for Edwards and scheduled monthly biopsies to make sure his body was not rejecting his organs.

“I was readmitted for another month or so after a biopsy went south,” said Edwards. “I began bleeding internally during the procedure, causing me to wake up choking on my own blood on the table. I was placed on life support for three days. Since then, I’d say it’s been uphill with slow, but positive progress.”

Edwards was never one to complain during his illness. He even managed to keep most of his coworkers from noticing anything was wrong except his sluggish ascent of the stairs at the facility. Only the people close to him or who saw him transporting his oxygen tank around knew something was up. He continued working until the week of his transplant, remaining in constant communication with his supervisors and the flight surgeon to ensure all necessary information about his condition was relayed.

“Once my NATCA colleagues did find out, they were amazingly supportive,” said Edwards. “Through donations, leave donations, meals, and just coming by to help pass the time, I really can’t thank them enough. Upper management and NATCA made it clear that whatever I needed, they were there for me. I want to thank everyone at work in NATCA, upper management, human resources — I mean everybody — for making my job security and the financial side of this challenge a non-factor.”

Edwards credits some of his recovery success and return to work to his experience as a controller, saying that the mental toughness that comes with the job helped him stay on track and never give up. Lung transplants do not typically have high success rates and the love and support he received, as well as his addition to the Voluntary Leave Transfer Program (VLTP), helped him stay focused on his recovery, which will continue over the course of the next three-to-eight years.

“I’d like to send a special thanks to my wife, my mother, my transplant team, the Hicks family, and everyone at ZHU,” concludes Edwards on his incredibly story of strength and resilience. “To my son Gavin, I love you. You are my inspiration.”