NATCA and the FAA Reach First CBA

As NATCA took its first steps with the FAA, the membership was nervous. When NATCA formed a steering committee to develop a joint labor-management cooperative with the FAA, it proved to be a groundbreaking charge for the group. Work with the steering committee revealed differences within NATCA on what the union’s main issues should be: traditional labor management relations or “new” initiatives.

Collaboration was not the norm in the union’s early days and much of the membership did not understand it. After the FAA denied NATCA’s proposed memorandum to provide 100 percent official time for regional representatives to carry out their union duties, Bell urged the steering committee not to “jump ship and become a strictly confrontational union.” Undeterred, NATCA remained resolute and put together a contract team that began drafting a new FAA-NATCA agreement. While the new agreement was built on PATCO’s last agreement with the FAA, the pact also broke new ground.

|

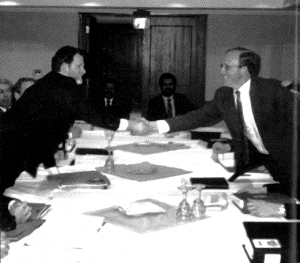

| NATCA President Steve Bell (right) and FAA Deputy Director of Labor and Employee Relations Ray Thoman. |

The first meeting took place on Nov. 16, 1988, and was the first bargaining talk between a controllers’ union and the Agency in more than seven years. At the negotiating table, Ray Thoman, the FAA Deputy Director of Labor and Employee Relations at the time, slid the FAA’s proposed collective bargaining agreement to Bell. Union Contract Team Co-Chairman Mark Kutch watched.

“Thank you very much,” Bell responded, sliding an even thicker document back to Thoman. “We know how hard you must have worked on this. We’d like to work off ours.”

Thoman responded by saying, “I thank you for your efforts. It was obviously a lot of work. But it is a sophomoric attempt because of your lack of expertise in this area.”

Though the NATCA reps in the room were in fact controllers who lacked business experience, the historic nature of the moment was not lost on the group. They understood their responsibility of helping to ensure the well-being of more than 13,000 families. Furthermore, they were prepared.

NATCA chose its 10-member contract team carefully, making sure it represented a balance of terminals and centers located across the regions. The team attended a two-day seminar on negotiating skills conducted by the American Arbitration Association. They also spent two intensive weeks at MEBA’s expansive colonial-style training facility in Easton, Md., drafting proposals and listening to advice from ousted PATCO President John Leyden so as not to repeat the mistakes of the past.

The contract team spent many late nights digging through PATCO archives, Office of Personnel Management regulations, FAA orders, grievance files and arbitration transcripts, private-sector entitlements, and federal-sector contracts for all bargaining units. Their research culminated in a comprehensive proposal containing 82 articles.

Bell remained confident, ignoring Thoman’s jab, and began to outline the union’s proposal. Parts of the document had roots in PATCO’s 1978 contract, including provisions for mandatory breaks after two hours on position, reinstatement of immunity for controllers who reported operational errors, and official release of union representatives for NTSB accident investigations.

Other sections were new, such as the union’s right to conduct midterm bargaining and guaranteed leave for prenatal care. The proposal also included workplace articles such as prime time leave and a uniform dress code, aimed at addressing inconsistent policies.

One notable provision that would be a gain for the union involved reporting immunity. NASA created the Aviation Safety Reporting System in 1975 to allow controllers, pilots, and others to document errors within 10 days of an incident without fear of penalty (except in cases of gross negligence or criminal activity). The system was designed to document common mistakes, which could help lead to procedures to avoid them.

Thoman insisted the provision was non-negotiable and did not belong in the contract. Krasner countered that they should include it for educational purposes. Thoman eventually agreed, which ensured that the FAA could not unilaterally change or abolish the policy because the union could contest the move by filing a grievance.

The first NATCA contract differed from PATCO’s last contract in several ways. Under the NATCA contract, the FAA negotiated the right to change controllers’ schedules within one week. Under the PATCO contract, it had been three weeks. Under the NATCA contract, developmentals had to check out on at least two control positions before receiving FAM trip privileges while PATCO trainees received the benefit immediately. But NATCA made one significant improvement over PATCO: the FAA agreed to grant regional representatives 50 percent of official time off to conduct their duties. PATCO board members who took leave to serve the union had done so without pay from the FAA.

The two sides reached a tentative agreement in mid-January 1989 after contract team members had spent two exhausting months negotiating in the Washington, D.C. area, far from their families. However, the work was not done.

| NATCA team members following negotiations: NATCA President Steve Bell; Co-Chairman Mark Kutch, Kansas City Center; Richard Bamberger, San Diego Tower; Don Carlisle, Washington Center; Paul Cascio, Seattle TRACON; Anthony Coiro, South Bend Tower/TRACON; Art Joseph, Miami Center; Lonnie Kramer, Corpus Christi Tower/TRACON; Barry Krasner, New York TRACON; William Osborne Jr., general counsel; and eight resource specialists. |

After negotiations, half of the union contract team joined Bell and Spickler on different segments of a tour to 23 cities to sell the contract to the members. The briefings tour helped educate the members but was costly. With little money to spare at the time, the union drew criticism from some who accused NATCA’s top officers of wasting money in what they coined as “Steve and Ray’s Excellent Adventure.” However, most controllers saw the value in educating the workforce.

Union members overwhelmingly approved of the contract. The three-year agreement took effect May 1, 1989, after the membership ratified it by a vote of 3,920 to 748 — an approval margin of 84 percent. Though subsequent contracts would further strengthen and expand controllers’ rights, NATCA founders and activists who’d spent more than five years creating the union and securing its first collective bargaining agreement basked in an enormous sense of accomplishment.