May 5, 2017 // A Course Correction by Cleveland Controllers

|

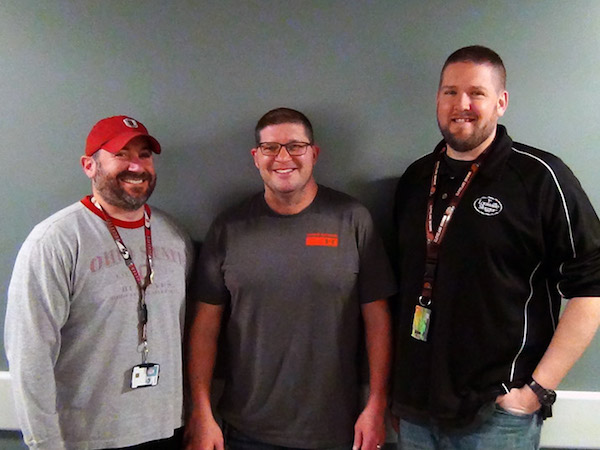

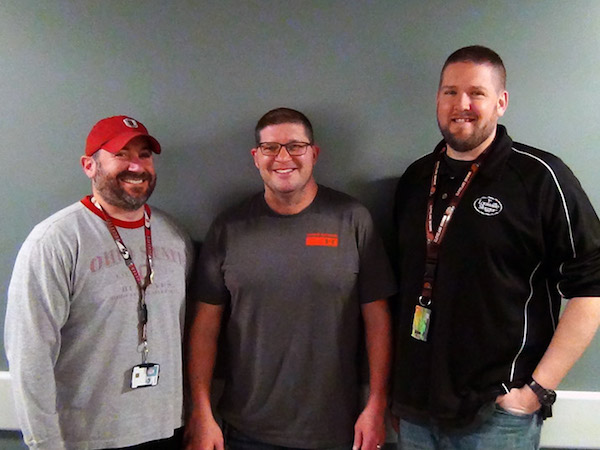

| Cleveland Tower air traffic controllers Dan Mitchell, Robert Haibach, and Dan Leipold collaborated with Andrew Gupko (not pictured) on a recent flight assist. Photo courtesy of the FAA. |

The close proximity of satellite airports to major airports adds to the challenges of air traffic control in metropolitan areas, a reality that recently hit home for controllers in Cleveland. Their situational awareness and quick action diverted two aircraft from a potential collision course.

Cleveland Tower (CLE) controllers Andrew Gupko, Robert Haibach, Dan Leipold, and Daniel Mitchell worked together to prevent an accident. It was good experience for Gupko, who was being trained by Leipold at the time. “They were definitely on top of it,” Operations Supervisor Francis Scalley said of his team’s efforts.

|

| Burke Lakefront Airport. |

Cleveland Hopkins International is the primary airport in the city. It is about 11 miles southwest of Burke Lakefront, the satellite airport along the shore of Lake Erie. In addition to the airports being close to each other, the runways at both facilities are on the same compass heading.

Because of the runway alignment and proximity of the airports, aircraft need to follow clearly defined procedures to ensure safe separation between them. Departing aircraft from Burke Lakefront climb to an assigned altitude and then veer right over the lake, thus avoiding planes that are approaching Cleveland Hopkins at a safe flight level parallel to and above them.

“When [Burke Lakefront departures] bust that altitude, they’re right underneath somebody on our [instrument landing system],” said Jim Ulry, NATCA CLE FacRep. “This does happen, but it’s rare.”

The evening of Jan. 12 was one of those rare times.

The trouble started soon after a Beechcraft Baron 58 took off from Burke Lakefront. Gupko was working traffic in a training scenario involving departures and uncontrolled traffic from the satellite airport while Leipold observed.

Leipold noticed that the Baron kept climbing after reaching 2,000 feet, the altitude at which the pilot should have turned toward Lake Erie. At the same time, a McDonnell Douglas MD-80 flown by American Airlines was descending toward Cleveland Hopkins.

“By this aircraft not turning and climbing,” Leipold said, “he was now paralleling the Cleveland Hopkins arrival with an aircraft on final and not aware of the other aircraft.”

At Leipold’s direction, Gupko contacted the Baron’s pilot, but he didn’t respond. Leipold then called Burke Lakefront Tower to alert them to the situation.

“They were surprised we were not talking to the aircraft,” Leipold said.

At that point Leipold keyed into the radio to take over for Gupko. He also leaned over to Mitchell, the controller for arrivals, and informed him that the Baron was not doing what it was supposed to do. Mitchell then contacted Haibach, the local controller, so he could reach out to the other pilot.

|

| Cleveland Hopkins International Airport. |

Haibach instructed the American Airlines pilot to climb to 4,000 feet. Meanwhile, he contacted the Baron pilot, telling him to descend to 2,000 feet and turn north. Both pilots responded.

“It worked exactly how it should work,” Leipold said. “We got the aircraft that we could control out of the situation.”

The aircraft came within three-fourths of a mile and 300 feet in altitude. The Baron pilot later called Cleveland Tower to discuss the incident and said he wasn’t able to turn because of a problem with his gyroscope. The tower also experienced frequency problems.

“A lot of little things went wrong in that minute-and-a-half,” Leipold said, but everyone responded well as a team. “This really isn’t, to me and probably anybody who worked that night, a big deal.”

Although controllers don’t like to see such scenarios develop, they periodically do, so in that sense it was a good training situation for Gupko.

Ulry said Leipold, a 10-year FAA veteran who also worked as a military controller for four years, was an ideal teacher. “Dan is a great guy, outgoing, great controller — one of the better trainers we have here,” Ulry said.

This story is being jointly published by the FAA and NATCA.